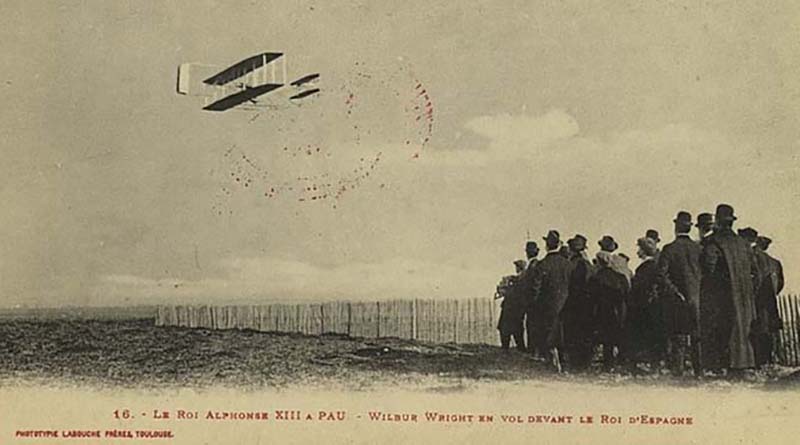

While our patent application was pursuing its slow course through the Patent Office, we built a second machine and flew it in a field near the city of Dayton, Ohio, in the summer and autumn of 1904. When we had familiarized ourselves with the operation of the machine in more or less straight flights, we decided to try a complete circle. At first we did not know just how much movement to give in order to make a circle of a given size. On the first three trials we found that we had started a circle on too large a radius to keep within the boundaries of the small field in which we were operating. Accordingly a landing was made each time, without accident, merely to avoid passing beyond the boundaries of the field. On the fourth trial, made on the 20th of September, a complete circle was made, and the machine was brought safely to rest after having passed the starting point. Thereafter we repeatedly made circles, and on the 29th of November made four circles of the field in a flight lasting a few seconds over five minutes….

With this machine we made approximately a hundred flights in the year 1904. Usually the machine responded promptly when we applied the control for restoring lateral balance, but on a few occasions the machine did not respond promptly and the machine came to the ground in a somewhat tilted position. The cause of the difficulty proved to be very obscure and the season of 1904 closed without any solution to the puzzle. In 1905 we built another machine and resumed our experiments in the same field near Dayton, Ohio. Our particular object was to clear up the mystery which we had encountered on a few occasions during the preceding year. During all the flights we had made up to this time we had kept close to the ground, usually within ten feet of the ground, in order that in case we met any new and mysterious phenomenon, we could make a safe landing.

With only one life to spend we did not consider it advisable to attempt to explore mysteries at such great height from the ground that a fall would put an end to our investigations and leave the mystery unsolved. The machine had reached the ground, in the peculiar cases I have mentioned, too soon for us to determine whether the trouble was due to slowness of the correction or due to a change of conditions, which would have increased in intensity, if it had continued, until the machine would have been entirely overturned and quite beyond the control of the operator. Consequently it was necessary or at least advisable to discover the exact cause of the phenomenon before attempting any high flights.

For a long time we were unable to determine the peculiar conditions under which this trouble was to be expected. But as time passed we began to note that it usually occurred when we were turning a rather short circle. We, therefore, made short circles sometimes for the purpose of investigating and noting the exact conduct of the machine from the time the trouble began until the landing was made…. The remedy was found to consist in the more skillful operation of the machine and not in a different construction. The trouble was really due to the fact that in circling, the machine has to carry the load resulting from centrifugal force, in addition to its own weight…. The machine in question had but slight surplus of power above what was required for straight flight, and as the additional load, caused by circling, increased rapidly as the circle became smaller, a limit was finally reached beyond which the machine was no longer able to maintain sufficient speed to sustain itself in the air….

In other words, the machine was in what has come to be known as a “stalled” condition. The phenomenon is common to all aeroplanes in the world and is the cause of frequent disaster to unskilled aviators. Our own machine is still subject to the same trouble. Within the last year [1911] four or five Wright machines have been wrecked by novices stalling the machines in attempting to climb too fast while circling, and have come tumbling to the ground, just as we did in 1905…. The remedy for this difficulty lies in more skillful operation of the aeroplanes. When we had discovered the real nature of the trouble, and knew that it could always be remedied by tilting the machine forward a little, so that its flying speed would be restored, we felt that we were ready to place flying machines on the market. — Wilbur Wright, quoted in Ron Geibert’s book Kitty Hawk and Beyond: The Wright Brothers and the Early Years of Aviation: A Photographic History (read for free)