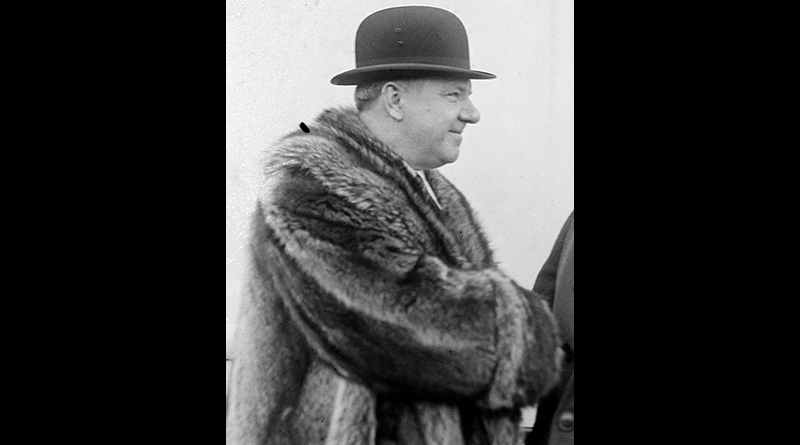

One afternoon when he was nine, W.C. Fields sneaked into the gallery of a vaudeville house and watched a performance of the Byrne Brothers, jugglers. He was electrified. He ran home and, with several lemons and oranges lifted from the cart, set up shop in the stable. Juggling, he found, was a perverse enterprise. “By the time I could keep two objects going, I’d ruined forty dollars’ worth of fruit,” he told a friend later. Fields’ homework with the fruit opened new vistas of discord between him and his father. Their mutual disapproval ripened fast. Dukinfield would crouch in the stable, then, if he caught the boy bruising lemons, he would prance out and give him a hiding. A crisis was reached not long after Fields’ eleventh birthday. He had left a small shovel lying in the front yard, and Dukinfield stepped on it. The handle flew up and banged him on the shin.

Unfortunately, the father had barked the same shin earlier that day on a hubcap of the vegetable cart. He hopped around on one leg awhile, cursing, then, seeing Fields studying him in a detached sort of way, he picked up the shovel and rattled it off the boy’s head. During the next few days Fields devoted himself to getting even. He said afterward that he rejected several plans certain to arouse the interest of the coroner and settled on a simple but effective reprisal. Holding a large wooden box poised aloft, he hid in the stable. His father came in, looking for trouble. Fields crowned him. Then he walked off down the road and never returned.

The first night of Fields’ exodus he slept in a hole in the ground — a “bunk,” covered over with boards and dug by his gang — in a field a mile from home. It was tolerably comfortable, as accommodations of this sort went, but toward morning the rain came down and the bunk began to leak pretty freely. By morning it had most of the earmarks of a hog wallow, and Fields began to be sorry he had left. When the sun rose over the treetops, he climbed out, after a couple of false starts, scraped off the topsoil, and lay down in the grass to dry off. He felt creaky and rheumatic, he said later, but the sun soon revived his prejudice against being hit with shovels. And now a new worry came up — he was hungry. After a while he crawled over behind some bushes near the road and awaited developments. Around nine o’clock a colleague known by the affectionate name of “Pot-head” Edwards came along on his way to school. Fields called hoarsely from the shrubs, explained his plight, and invoked aid. It was not long forthcoming. As they took their meals, the fugitive’s friends, like Pip supplying the convict in Great Expectations, secreted a bun here and a parsnip there, and made for the bunk as soon as they escaped surveillance. They looked up to Fields. They were proud of his indifference to authority.

Fields’ family made little more than a token search. His mother felt that, at eleven, he was young to set up on his own, but the problems of four other children diverted her mind. The attitude of Fields’ father could perhaps be summed up by the handy phrase “good riddance.” He took the stand that a boy careless with small shovels would likely grow up to be careless with large shovels, and that such a person was a menace. He trained another of his offspring to help out on the cart. For years thence neither Dukinfield nor his wife knew where their son had gone. Meanwhile, the boy had begun to enjoy himself. There being no other place available at the moment, he tightened the bunk’s defenses against weather, stole a quilt off a neighbor’s line, and bought some candles with a dime he had borrowed from an admirer. At the same time, his friends continued to bring food. Adequately housed, well stoked, and having no connection with vegetables and fruit save as consumer, Fields felt at peace for the first time in years.

The idyll was short-lived. The day he had fled, in March, was balmy for that season. Less than a week later the weather turned surly, and he found the quilt insufficient. To heat things up, he made a small bonfire in one corner of the bunk, but it caused such a smudge and hurt his eyes so badly that he covered it with mud. He spent one night wrapped in the quilt and huddled over a candle. When he surfaced the next morning it was snowing briskly. About this time, the participants in his food lift gave up, for the most part. The novelty had worn off, and several of them, caught greasy-handed, had been soundly trounced. Their loyalty to Fields was solid, but it fell short of corporal punishment. The time had come, Fields felt, to move into a better neighborhood. He discovered that it was a period in which the kind of housing he sought — free and removed from the scrutiny of police — was extraordinarily scarce.

— Robert Lewis Taylor, in his book W.C. Fields, His Follies and Fortunes