In writing her memoirs, Bernhardt did not bother to clear up speculations and rumors regarding her parents and their origins. Her Jewish mother, Judith, might have come from Germany or Holland. Her father might have been Paul Morel, a French naval officer, as listed in some official documents. Or, perhaps he was Edouard Bernhardt, a brilliant young French lawyer whose name her mother adopted. Bernhardt referred to her father only as “father.”

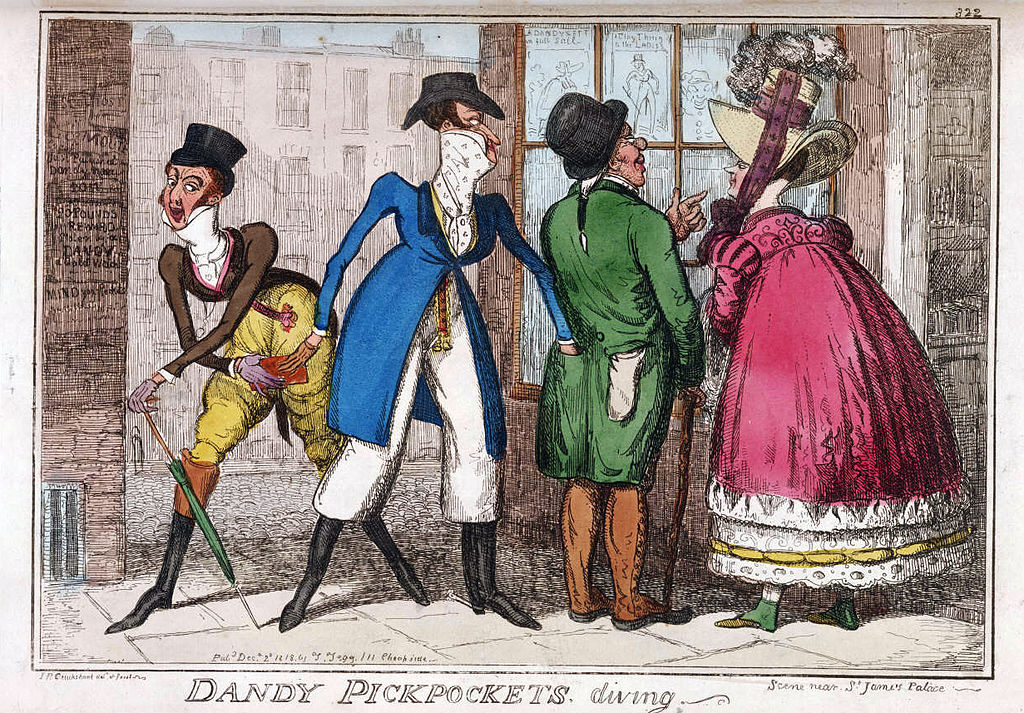

When Sarah was born on October 23,1844, Judith was only 16 years old. A beautiful girl with a lovely face and figure, Judith had been a milliner before arriving in France to seek her fortune. Perhaps she could have become a governess or a seamstress, but she thought either option was too dull and poorly paid. In the 1840s, among the aristocracy and nobility of Paris, a clever, attractive young woman could set herself up as a courtesan if she could attract wealthy patrons to support her lifestyle. It was almost a respectable profession; many people admired these women who knew how to entertain lavishly, dress elegantly with style and grace, appreciate art and the theater, and please the men who sponsored them. It was a precarious position and one that required constant close attention. Being able to travel about Europe with one’s current lover was also necessary. A demanding baby was not an asset.

Judith’s solution was to send Sarah to live with a wet nurse in Brittany, a considerable distance from Paris. The nurse called her Milk Blossom, the only name Sarah knew during her early years. The woman was a good-hearted, illiterate farm peasant, who cared for the child as well as she knew how. One day, when the nurse had been called to work in the fields, she left the baby Milk Blossom in a highchair under the care of her invalid husband. Sarah soon managed to work her way out of her highchair and rolled onto the edge of the blazing fireplace, where her clothing caught fire.

Alerted by the bedridden husband’s screams, neighbors rushed in and dumped the smoking baby in a pail of fresh milk. Then all the neighbors brought butter to make poultices to put on the delicate burned skin. Sarah’s aunts were notified and managed to reach her mother, who was traveling in Belgium with Baron Larrey, who served as physician to Emperor Napoleon III. Soon a succession of elegant carriages arrived in front of the humble cottage. Sarah’s account of the incident reveals her understanding of the nature of this mother from whom she could never win the unconditional love she craved:

Mama, ravishingly beautiful… gave money to everybody. She would have given her golden hair, her childlike feet, and her very life to save this child about whom she had been so little concerned only a week before. Yet she was just as sincere in her despair and her love as she had been in her unconscious forgetfulness. (My Double Life)

For six weeks, Judith, her sister Rosine (an even more notorious courtesan than Judith), and a young doctor stayed while Sarah recuperated from the accident. Then Judith moved Sarah, along with the nurse and her husband, to a cottage in Paris on the banks of the River Seine and resumed her travels. She asked Sarah’s aunts to look in on the child, but they were too busy to take the time. Judith herself sent money, candy, and toys. For the next few years, the rough peasants were the only family Sarah knew. When the nurse’s husband died, she married a concierge. Not knowing how to write and not having an address for Judith, the nurse moved her five-year-old charge to a new home without informing anyone.

The new home was situated at the entrance of a large estate. After living near the sea and a river, the huge gray stones of the gateway and lack of windows in the house depressed the sensitive child, who found the setting dark and ugly. Sarah lost her appetite and grew pale and anemic. Through a strange coincidence, she was rescued from this dismal life in what she later deemed a miracle.

One day as she was playing in the courtyard, she heard a familiar voice and looked up to see the concierge showing two elegant ladies about the estate grounds. Her thin little body began to shake as she recognized her aunt Rosine. Throwing herself at her aunt, she buried her face in her furs, laughing, sobbing hysterically, and ripping her lace sleeves. Amazed at finding her niece in this place, Aunt Rosine stroked her hair and tried to calm her. Then she emptied the contents of her purse into the hands of the nurse and promised to come back for Sarah the next day.

But Sarah had learned not to trust the promises of adults in her life, and she did not believe this playful, charming, self-centered aunt. As the good nurse held the distraught child to a window to watch her aunt’s departure, the nurse tried to convince Sarah that her aunt would return. In a fit of despair, Sarah hurled herself from the nurse’s arms onto the pavement at her aunt’s feet. She awoke in a large, sweet-smelling bed in a bedroom with large windows. She had broken her arm and her kneecap, but she had escaped her dreary surroundings. Her mother returned once again from her travels to care for her daughter. It took two years for the fragile child to recover from the terrible fall and her run-down condition. During that time, she was happy to receive all the cuddling and love that was offered her in her aunt’s and her mother’s lively households. — Elizabeth Silverthorne, in the biography Sarah Bernardt

***

My mother was very gentle but determined, and this determination of hers ended sometimes in the most violent anger. She used then to turn very pale, and violet rings would come round her eyes, her lips would tremble, her teeth chatter, her beautiful eyes take a fixed gaze, the words would come at intervals from her throat, all chopped up — hissing and hoarse. After this she would faint; and the veins of her throat would swell, and her hands and feet turned icy cold. Sometimes she would be unconscious for hours, and the doctors told us that she might die in one of these attacks, so that we did all in our power to avoid these terrible accidents. My mother knew this, and rather took advantage of it, and, as I had inherited this tendency to fits of rage from her, I could not and did not wish to live with her. As for me, I am not placid. I am active and always ready for fight, and what I want I always want immediately. I have not the gentle obstinacy peculiar to my mother. The blood begins to boil under my temples before I have time to control it. Time has made me wiser in this respect, but not sufficiently so. I am aware of this, and it causes me to suffer. — Sarah Bernhardt, in her autobiography My Double Life: The Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt