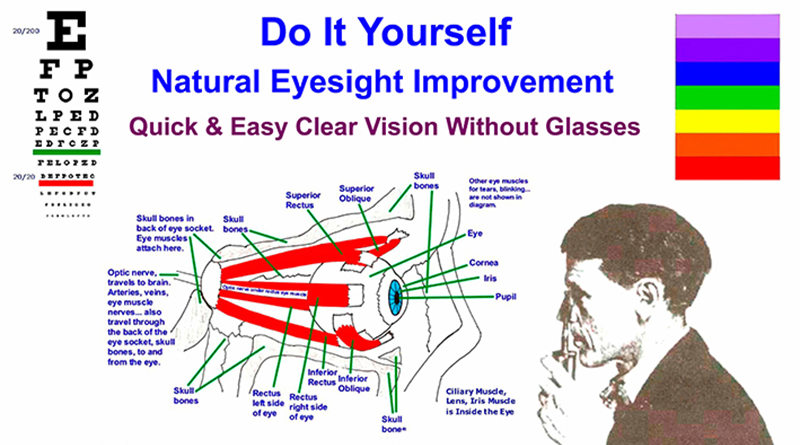

It was not until I was seven that I became embarrassed by my father’s lack of self-consciousness. He had just discovered the Bates ‘better sight without glasses’ book and method. One exercise involved rolling the eyeballs in order to strengthen the internal muscles of the eye. Another, called ‘palming’, required one to place one’s palms over both eyes and to imagine a starless night or black velvet. When my father chose to do these exercises, sitting beside me on a District Line train en route to Dorking via Wimbledon, I sat in silence, cheeks burning, convinced that our fellow passengers would think him crazy.

When I travelled with my mother on the tube or bus, things would be very different. Sometimes, she would nudge me surreptitiously, indicating some comically dressed person, and then greatly enjoy my difficulties as I fought to keep a straight face. She herself could remain composed after saying the most outrageous things. If I’d ever laughed out loud, she would have told me I was being extremely rude, and would have meant it. While I might enjoy the sight of a fat man in a tight suit, and be entertained to see some elderly woman grotesquely made-up, I soon felt mean for being amused and thought of what my father would have said to me if he knew. He always found he had things in common with people, and never smiled at their expense. I liked this. But I also admired my mother’s ability to look so innocent while making her funny and mischievous remarks.

One day, while standing with my father in Wimbledon Station near the glass case containing the stuffed dog that stood on the platform right through the 1950s, I told him how much it worried me when he did the Bates exercises in public. He looked flabbergasted.

‘People might laugh at you,’ I explained.

‘I wouldn’t mind if they did.’

‘But I mind, daddy.’

‘Do you really see people staring at me? What sort of person would do that?’

I thought of my mother. My father looked quite unhappy now. I wanted to tell him it was because I loved him that I cared what people thought. But just then the train came in, and soon we were with other people. I knew he had the Bates book with him and now felt he couldn’t read it because I would get upset. I started to feel guilty. Maybe if people had noticed him rolling his eyes, it wouldn’t have mattered. When we were approaching Dorking, I reached out a hand and was relieved he took it. — Tim Jeal, in his book Swimming with My Father: A Memoir (read for free)