In an American paper I find this anecdote: “An old lady was being shown the spot on which a hero fell. ‘I don’t wonder,’ she replied. ‘It’s so slippery I nearly fell there myself.'”

Now that story, which is very old in England, and is familiar here to most adult persons, is usually told of Nelson and the Victory. Indeed it is such a commonplace with facetious visitors to that vessel that the wiser of the guides are at pains to get in with it first. But in America it may be fresh and beginning a new lease of life; it will probably go on forever in all English-speaking countries, on each occasion of its recrudescence finding a few people to whom it is new.

It is a problem why we tend to be so resentful when an editor or a comedian offers us a jest that has done service before. It is, I suppose, in part at any rate, because we have paid our money, either for the paper or the seat, and we experience the sense of having been defrauded. We have been done, we feel, because the bargain, as we understood it, was that we were purchasing novelty. So that when suddenly an old, old jape, which perhaps we have ourselves related — and that of course is an aggravation of the grievance — confronts us, we are indignant. But what, one wonders, would a comic paper or a revue that had nothing old in it be like. We can never know.

The odd thing is that we not only resent the age of the joke, even though it is in our own repertory, but we resent the laughter of those to whom it is new — perhaps three-quarters of the audience. How dare they also not have heard it before? is our unspoken question. Not long ago, seated in a theatre next a candid and normally benignant and tolerant friend, I found myself laughing at what struck me as a distinctly humorous remark made by one of London’s nonsensical funny men. Engaged in a competition with another as to which had the longer memory, he clinched the discussion by saying that he personally could remember London Bridge when it was a cornfield. To me that was as new as it was idiotic, and I behaved accordingly; but my friend was furious with me. “Good heavens!” he exclaimed with the click of the tongue that usually accompanies such criticism, “fancy digging that up again! It’s as old as the hills.” And his face grew dark and stern.

What we have to remember, and what might have softened my friend’s granite anger had he remembered it, is that a new audience is always coming along to whom nothing is a chestnut. It is not the most reassuring of thoughts to those who are a little fastidious about ancientry in humour; but it is nature and therefore a fact. Just as every moment (so I used to be told by a solemn nurse) a child is born (she added also that every moment some one dies, and she used to hold up her finger and hush! for me to realise that happy thought), so nearly every moment (allowing for a certain amount of infant mortality) an older child attains an age when it can understand and relish a funny story. To those children every story is original. With this new public, clamorous and appreciative, why do humourists try so hard to be novel? (But perhaps they don’t).

I suppose that there are theories as to what is the oldest story, but I am not acquainted with them. That people are, however, quite prepared for every story to be old is proved by the readiness with which, when Mark Twain’s “Jumping Frog” was translated into Greek for a School Reader, a number of persons remarked upon the circumstance that the humourist had gone to ancient literature for his jest. For by a curious twist we are all anxious that stories should not be new. Much as we like a new story, we like better to be able to say that to us it was familiar.

Many stories come rhythmically round again. Such, for example, during the Great War, as those with a martial background. I remember during the Boer War hearing of a young man who was endeavouring to enlist, and was rejected because his teeth were defective. “But I want to fight the Boers,” he said, “not eat them.” Between 1914 and 1918 this excellent retort turned up again, only this time the young man said that he did not want to eat the Germans. I have no doubt that in the Crimean War a similar applicant declared that he did not want to eat the Russians, and a hundred years ago another was vowing that he did not want to eat the French. Probably one could trace it through every war that ever was. Probably a young Hittite with indifferent teeth proclaimed that his desire was to fight the Amalekites and not to eat them. The story was equally good each time; and there has always been a vast new audience for it. And so long as war continues and teeth exist in the human head, which I am told will not be for ever, so long will this anecdote enjoy popularity. After that it will enter upon a new phase of existence based upon defects in the applicant’s râtelier [dentures], and so on until universal peace descends upon the world, or, the sun turning cold, life ceases.

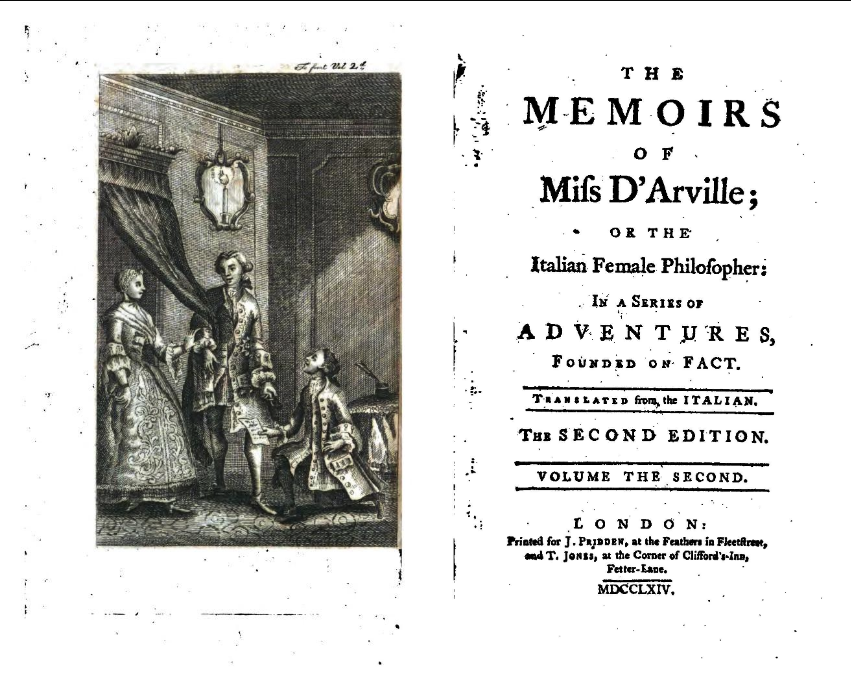

— Adventures and Enthusiasms (published 1920), by Edward Verrall Lucas.