XXI.

Sydney Smith (1771–1845), the witty and brilliant editor of the Edinburgh Review, was a favorite in society and an intellectual leader of his time. As a preacher in London he was exceedingly influential, and his Plymley Letters helped to further the movement for Catholic emancipation. The Lady Georgiana Morpeth to whom this letter is addressed was the wife of the Earl of Carlisle, and the mother of a boy whom Smith had tutored in Edinburgh.

Sydney Smith to Lady Georgiana Morpeth

FOSTON, Dec. 1st, 1821.

Dear Lady Georgiana, —

How is Lord Carlisle? Pray do not take it for inattention that I do not call oftener, but it is rather too far to walk, and I hate riding. Next year I shall set up a gig, and then I shall call at Castle Howard twice a day all the year round, like an apothecary. I have just finished Miss Aitkin’s Memoirs of Queen Elizabeth, a pretty book, which I counsel you to let your daughters read, if they have not read it five years ago. I am in low spirits about the Malton road. I must go over to Malton so often, and it will be so troublesome. All my hay-stacks and corn-ricks are blown away by this wind, two of my maids are married, and the pole of my carriage is broken! These are the sort of things which render life so difficult.

Yours, dear Lady Georgiana,

Sydney Smith.

XXIII.

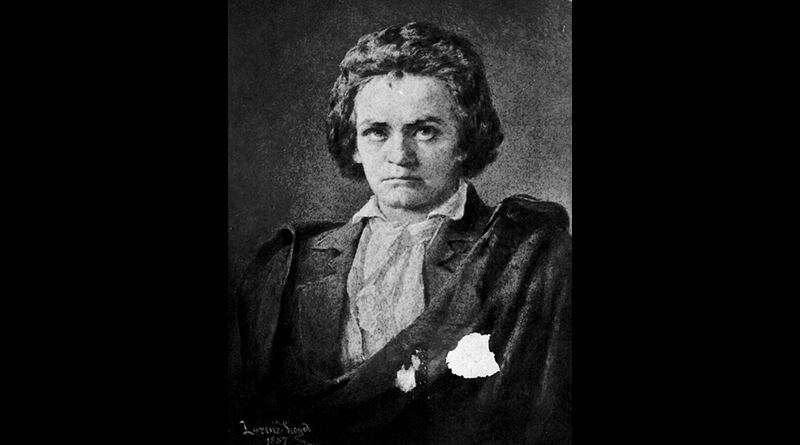

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834), the author of The Ancient Mariner, was a poet of marvelous endowment who became a slave to opium and, under the influence of German thinkers, devoted much of his life to philosophical and theological speculation, thus disappointing the hopes of those who knew his splendid imaginative and poetic power. He was a brilliant conversationalist, and numbered among his friends Lamb, Southey, Wordsworth, and other able men of his time, during his later years becoming the center of a group of talented disciples. This letter, written to Godwin, the father-in-law of Shelley and the author of Political Justice, illustrates Coleridge’s weakness and the vagaries of his intellect.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge to William Godwin

At Mr. Lamb’s, 36, Chapel Street, March 3, 1800.

Dear Godwin, —

The punch, after the wine, made me tipsy last night. This I mention, not that my head aches, or that I felt, after I quitted you, any unpleasantness or titubancy; but because tipsiness has, and has always, one unpleasant effect — that of making me talk very extravagantly; and as, when sober, I talk extravagantly enough for any common tipsiness, it becomes a matter of nicety in discrimination to know when I am or am not affected. An idea starts up in my head, — away I follow through thick and thin, wood and marsh, brake and briar, with all the apparent interest of a man who was defending one of his old and long-established principles. Exactly of this kind was the conversation with which I quitted you. I do not believe it possible for a human being to have a greater horror of the feelings that usually accompany such principles as I then supposed, or a deeper conviction of their irrationality, than myself; but the whole thinking of my life will not bear me up against the accidental crowd and press of my mind, when it is elevated beyond its natural pitch. We shall talk wiselier with the ladies Tuesday. God bless you, and give your dear little ones a kiss apiece from me. Yours with affectionate esteem,

S. T. COLERIDGE.

LI

Thomas Bailey Aldrich (1836-1907) writes to thank his friend, W. D. Howells, for a delightful visit at his home. This note, simple, informal, and graceful, should be compared with the solid sonorous letters of the early eighteenth century.

Thomas Bailey Aldrich to William Dean Sowells

Ponkapog, Mass., Dec. 13, 1875.

Dear Howells, —

We had so charming a visit at your house that I have about made up my mind to reside with you permanently. I am tired of writing. I would like to settle down in just such a comfortable home as yours, with a man who can work regularly four or five hours a day, thereby relieving one of all painful apprehensions in respect to clothes and pocket-money. I am easy to get along with. I have few unreasonable wants and never complain when they are constantly supplied. I think I could depend on you.

Ever yours,

T.B.A.

P.S. I should want to bring my two mothers, my two boys (I seem to have everything in twos), my wife, and her sister.

— Selected English Letters (published 1914), by Claude Moore Fuess (1885–1963), editor.