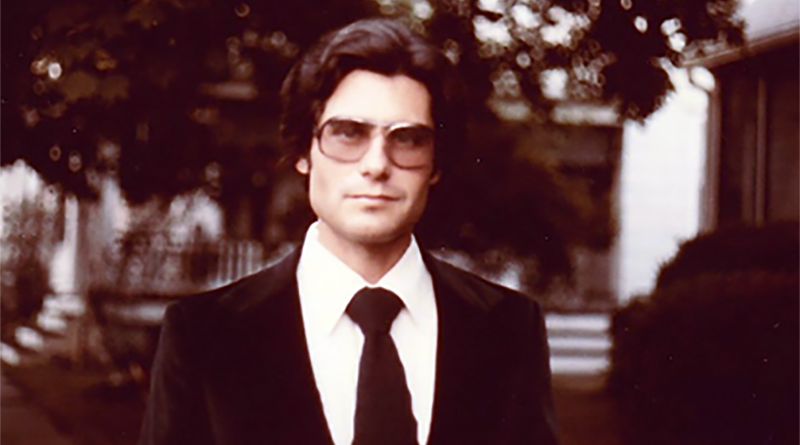

Until my incredible experiences with Catherine, the patient whose therapy is described in the book Many Lives Many Masters, my professional life had been unidirectional and highly academic. I was graduated magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, from Columbia University and received my medical degree from the Yale University School of Medicine, where I was also chief resident in psychiatry. I have been a professor at several prestigious university medical schools, and I have published over forty scientific papers in the fields of psychopharmacology, brain chemistry, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety states, substance abuse disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease. My only previous contribution to book publishing had been The Biology of Cholinergic Function, which was hardly a bestseller, although reading it did help some of my insomniac patients fall asleep. I was left-brained, obsessive-compulsive, and completely skeptical of “unscientific” fields such as parapsychology. I knew nothing about the concept of past lives or reincarnation, nor did I want to.

Catherine was a patient who was referred to me about a year after I had become Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami Beach, Florida. In her late twenties, a Catholic woman from New England, Catherine was quite comfortable with her religion, not questioning this part of her life. She was suffering from fears, phobias, paralyzing panic attacks, depression, and recurrent nightmares. Her symptoms had been lifelong and were now worsening.

After more than a year of conventional psychotherapy, she remained severely impaired. I felt she should have been more improved at the end of that time span. A hospital laboratory technician, she had the intelligence and insight to benefit from therapy. There was nothing in her basic makeup to suggest that her case would be a difficult one. Indeed, her background suggested a good prognosis. Since Catherine had a chronic fear of gagging and choking, she refused all medications, so I could not use antidepressants or tranquilizers, drugs I was trained to use to treat symptoms like hers. Her refusal turned out to be a blessing in disguise, although I did not realize it at that time.

Finally, Catherine consented to try hypnosis, a form of focused concentration, to remember back to her childhood and attempt to find the repressed or forgotten traumas that I felt must be causing her current symptoms.

Catherine was able to enter a deep hypnotic trance state, and she began to remember events that she consciously had been unable to recall. She remembered being pushed from a diving board and choking while in the water. She also recalled being frightened by the gas mask placed on her face in a dentist’s office…. I was certain that now we had the answers. I was equally certain that now she would get better.

But her symptoms remained severe. I was very surprised. I had expected more of a response. As I pondered this stalemate, I concluded that there must be more traumas still buried in her subconscious. We would try again.

The next week I once again hypnotized Catherine to a deep level. But this time, I inadvertently gave her an open-ended, nondirective instruction.

“Go back to the time from which your symptoms arise,” I suggested. I had expected Catherine to return once again to her early childhood.

Instead, she flipped back about four thousand years into an ancient near-Eastern lifetime, one in which she had a different face and body, different hair, a different name. She remembered details of topography, clothes, and everyday items from that time. She recalled events in that lifetime until ultimately she drowned in a flood or tidal wave, as her baby was torn from her arms by the force of the water. As Catherine died, she floated above her body, replicating the near death experience work of Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, Dr. Raymond Moody, Dr. Kenneth Ring, and others, work we will discuss in detail later in this book. Yet, she had never heard of these people or their work.

During this hypnosis session, Catherine remembered two other lifetimes. In one, she was a Spanish prostitute in the eighteenth century, and in another, a Greek woman who had lived a few hundred years after the near-Eastern lifetime.

I was shocked and skeptical. I had hypnotized hundreds of patients over the years, but this had never happened before. I had come to know Catherine well over the course of more than a year of intensive psychotherapy. I knew that she was not psychotic, did not hallucinate, did not have multiple personalities, was not particularly suggestible, and did not abuse drugs or alcohol. I concluded that her “memories” must have consisted of fantasy or dreamlike material. But something very unusual happened. Catherine’s symptoms began to improve dramatically, and I knew that fantasy or dreamlike material would not lead to such a fast and complete clinical cure. Week by week, this patient’s formerly intractable symptoms disappeared as under hypnosis she remembered more past lives. Within a few months she was totally cured, without the use of any medicines.

My considerable skepticism was gradually eroding. During the fourth or fifth hypnosis session something even stranger transpired. After reliving a death in an ancient lifetime, Catherine floated above her body and was drawn to the familiar spiritual light she always encountered in the in-between-lifetimes state.

“They tell me there are many gods, for God is in each of us,” she told me in a husky voice. And then she completely changed the rest of my life:

“Your father is here, and your son, who is a small child. Your father says you will know him because his name is Avrom, and your daughter is named after him. Also, his death was due to his heart. Your son’s heart was also important, for it was backward, like a chicken’s. He made a great sacrifice for you out of his love. His soul is very advanced … his death satisfied his parents’ debts. Also he wanted to show you that medicine could only go so far, that its scope is very limited.”

Catherine stopped speaking, and I sat in an awed silence as my numbed mind tried to sort things out. The room felt icy cold.

Catherine knew very little about my personal life. On my desk I had a baby picture of my daughter, grinning happily with her two bottom baby teeth in an otherwise empty mouth. My son’s picture was next to it. Otherwise Catherine knew virtually nothing about my family or my personal history. I had been well schooled in traditional psychotherapeutic techniques. The therapist was supposed to be a tabula rasa, a blank tablet upon which the patient could project her own feelings, thoughts, and attitudes. These then could be analyzed by the therapist, enlarging the arena of the patient’s mind. I had kept this therapeutic distance with Catherine. She knew me only as a psychiatrist, knew nothing of my past or of my private life. I had never even displayed my diplomas in the office.

The greatest tragedy in my life had been the unexpected death of our firstborn son, Adam, who was only twenty-three days old when he died early in 1971. About ten days after we had brought him home from the hospital, he had developed respiratory problems and projectile vomiting. The diagnosis was extremely difficult to make. “Total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage with an atrial septal defect,” we were told. “It occurs once in approximately every ten million births.” The pulmonary veins, which were supposed to bring oxygenated blood back to the heart, were incorrectly routed, entering the heart on the wrong side. It was as if his heart were turned around, backward. Extremely, extremely rare. Heroic open-heart surgery could not save Adam, who died several days later. We mourned for months, our hopes and dreams dashed. Our son, Jordan, was born a year later, a grateful balm for our wounds.

At the time of Adam’s death, I had been wavering about my earlier choice of psychiatry as a career. I was enjoying my internship in internal medicine, and I had been offered a residency position in medicine. After Adam’s death, I firmly decided that I would make psychiatry my profession. I was angry that modern medicine, with all of its advanced skills and technology, could not save my son, this simple, tiny baby.

My father had been in excellent health until he experienced a massive heart attack early in 1979, at the age of sixty-one. He survived the initial attack, but his heart wall had been irretrievably damaged, and he died three days later. This was about nine months before Catherine’s first appointment. My father had been a religious man, more ritualistic than spiritual. His Hebrew name, Avrom, suited him better than the English, Alvin. Four months after his death, our daughter, Amy, was born, and she was named after him.

Here in 1982 in my quiet, darkened office, a deafening cascade of hidden, secret truths was pouring upon me. I was swimming in a spiritual sea, and I loved the water. My arms were gooseflesh. Catherine could not possibly know this information. There was no place even to look it up. My father’s Hebrew name, that I had a son who died in infancy from a one-in-ten million heart defect, my brooding about medicine, my father’s death, and my daughter’s naming — it was too much, too specific, too true. This unsophisticated laboratory technician was a conduit for transcendental knowledge. And if she could reveal these truths, what else was there?

— Brian L. Weiss, in his book Through Time Into Healing