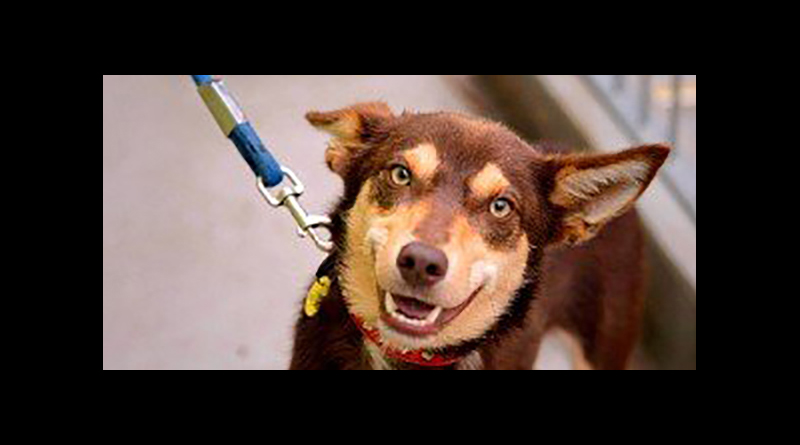

I found him sharing a cage with a reddish female counterpart in the boarding area of my vet’s hospital facility, where they had been sitting for five months, waiting patiently for someone who was never coming back. There they were: two seventy-five-pound dogs, a golden retriever and a flat-coated retriever, sharing a dog bed on the floor of a cell that was just slightly larger than the two of them. They seemed bored but otherwise in good health and sensibly cautious when I opened the cage. A few minutes after that, they both became very friendly. Once I agreed to “foster” them for a while, the staff at the vet’s office sighed with relief. They all knew it was out of character for me not to fall in love with any dog once I took him home.

Where do they think we’re going and who do they think I am? I asked myself as I led both dogs out to my car. I marveled at how they both jumped in without hesitation. After all, here I was, driving them to a place they’d never been where they might be spending the rest of their lives. Are they worried or disoriented? I wondered. They don’t really look stressed. Do they miss their original home? But by the time we arrived at my house, they seemed totally comfortable. Talk about a classic tale of death and rebirth: it was like they’d lived here their whole lives.

How did they manage to readjust so quickly? I mused. When a human being leaves a traumatic situation that involves abandonment and prison, it takes years of therapy to get past the pain, the trepidation, the hurt, the nightmares. Posttraumatic stress disorder, they call it. Yet these two went right to the communal water bowl, had a drink, then sat down in the living room next to my other two dogs and took a nap. When, a little while later, I got up to go to work in my office, all four of them followed me in like they’d done this a million times.

Thinking back on it now, I viewed the process with a certain amount of awe. In this era of economic strain, endless war, and environmental upheaval, might these two dogs have some worthwhile advice to offer about coping and readjusting? Enough time had passed, I supposed, for them to have gained some valuable insight.

I decided to ask them about it.

“Jimmy?” I said, calling to the flat-coated retriever. From my office desk chair, I could see him lying on his left side next to the closet, snoring.

He roused himself out of a deep sleep, sat up, and looked right at me. “Yes!” he said, coming over and sitting down beside me. “To all three questions. Yes, yes, and yes!”

“I didn’t ask you even one question yet,” I pointed out. “I just called your name. I have no idea what you think you are answering.”

“Will you come here, do you want to go for a walk, and do you want a cookie?” he said. “The three questions that are always implied when you call my name. And for the record, the answer to all three is always yes.” — Merrill Markoe, in her book Cool, Calm & Contentious (read for free)