In August 1874, backed by not only the New York Herald but also Britain’s Daily Telegraph, Stanley sailed once again for Zanzibar. With 347 porters, guides and dependants, laden with rifles, the expedition that marched for the Lualaba on 17 November was even bigger and more extravagant than the one he had raised to rescue Livingstone, and it followed the same pattern. Two of the three Britons Stanley took with him died after a few months; he himself was stricken by fever (by Christmas he was 42 pounds lighter than when he had left Zanzibar); the porters deserted, and when recaptured were flogged and chained; the column pillaged indiscriminately; and battle after battle was fought when the way was blocked. Stanley forced his men (and himself) to ever greater endeavour. After 103 days in the field he consulted his pedometer and discovered the column had covered 720 miles — a distance that he reckoned would have taken a standard caravan between nine months and a year.

Among the porters’ baggage were the five sections of the Lady Alice, a craft designed by Stanley, which was used to explore both Victoria Nyanza and Lake Tanganyika and which was reassembled in November 1876 when at last they reached the Lualaba. Anticipating trouble, Stanley acquired the support of a prominent Arab trader, whose 700 warriors turned the already well-armed expedition into a small army more than 1,000 strong. Thus reinforced, Stanley proceeded downriver to the Nile. Actually, he was uncertain whether the Lualaba led to the Nile or the Congo: from what he had seen and read, it seemed too powerful to be part of the Nile system. Nevertheless, having come so far, he was not going to turn back. In a morale-boosting speech he announced, ‘I am not going to leave this river until I reach the sea.’ His escort departed shortly thereafter.

Stanley’s journey, through territory no European had ever seen, was hard. He was attacked by tribesmen who fired poisoned arrows from the riverbank. Sometimes they came at him, 2,000 strong, in canoes. After one night ashore, Stanley found his camp had been quietly encircled by nets and a carpet of cane splinters. The attacks continued for a distance of more than 1,000 miles. Always, his well-armed force managed to blow its way through human opposition; nevertheless, the spears and arrows took a gradual toll on his men as did the river itself.

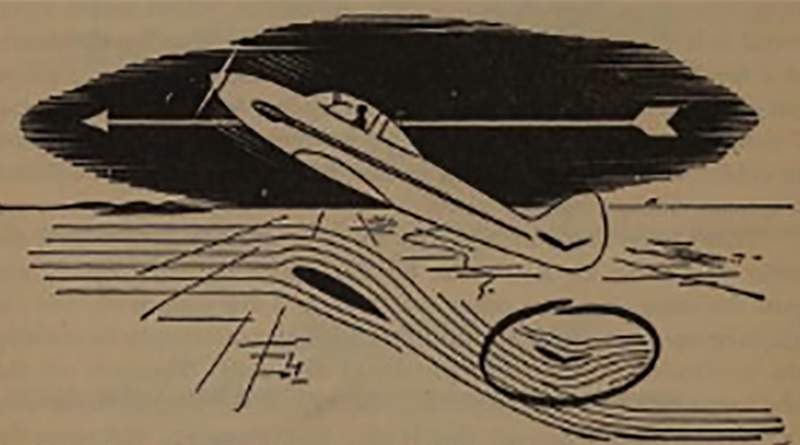

On 6 January 1877 the expedition met the first of a series of seven cataracts that extended, interspersed with rapids, for more than 50 miles. At every cataract the Lady Alice and its accompanying canoes — cumbersome, 50-foot lengths of hollowed-out tree trunk — had to be hauled overland using cables made of rattan creeper cut from the surrounding forest. By day they were tormented by ants; by night they toiled in the light of gum-soaked bundles of reeds. During the portages, and in the narrower stretches of rapids, they were attacked repeatedly; canoes overturned; men drowned, baggage and weapons were lost. After one particularly bad capsizing, three men were stranded on a rock on the very brink of a waterfall (one of them actually went over the edge, but at the last moment grabbed a rope thrown to him by his crewmates). Stanley described his predicament in dramatic terms: ‘A Fall 50 yards in width separated the island from us, and to the right was a Fall about 300 yards wide, and below them was half a mile of Falls and Rapids and great whirlpools and waves rising like hills in the middle of the terrible stream, and below these were the cannibals of Mane-Mukwa.’ It took a day and a night of failed attempts before Stanley finally flung the stranded men a line strong enough to bear their weight.

By the end of the month they were free of the cataracts (which Stanley felt justified in naming after himself) and on 7 February they enjoyed a day in which they did not have to kill someone.

That same day Stanley noted that the river (rechristened by him the Livingstone River) had taken a decisive turn to the west. It could not, therefore, be the Nile, but was as locals for the first time began to call it — the Congo. He continued downriver, in conditions that became ever more alarming. One day they fought a five-hour running battle against tribesmen who harried them from the banks and chased them in canoes. On another they strode through a deserted village strewn with skulls and bones that, to Stanley, displayed all the marks of cannibalism. Increasingly, their adversaries used muskets instead of bows — a good sign in that it meant they were within reach of European traders, but bad in that Stanley could no longer rely on the total superiority of his weapons. In mid-March, having survived a total of 32 major battles and countless minor skirmishes, the flotilla reached a pool 15 miles wide and 17 long where the locals, for once, seemed friendly. They had travelled 1,235 miles in 128 days, had lost half the 100 guns with which they had started, had used most of their ammunition and trade goods, and were reduced in number to less than 150. Pausing only to name their haven Stanley Pool (later to be the site of Stanleyville, capital of Belgian Congo and, across the river, Brazzaville, capital of French Congo), Stanley led his depleted force to the sea, as he had promised he would.

— Fergus Fleming, in his book Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration