(Photo: Groucho, Harpo, and Chico Marx) As far back as I can remember, my grandmother and grandfather lived with us in whatever Yorkville flat we happened to be occupying at the time. They had been performers in Germany — he a ventriloquist and she a harpist who yodeled while plucking the strings. His name was Lafe Schoenberg and her name was Fanny. (In those days the name Fanny still had vestiges of respectability.) When he was fifty they migrated to America.

Lafe lived to be a hundred and one, and in doing so thumbed his nose at all the rules of longevity. He smoked ten long black cigars a day; these he rolled from the leavings of a tobacco factory. Between cigars, he smoked a pipe that had all the fragrance of an old suit of heavy underwear burning in a damp cellar….

Lafe drank a pint of whiskey a day. This was not bonded bourbon, but a concoction made from the residue of a small distillery that was only too happy to give the stuff away….

Since neither my grandfather nor my grandmother spoke any English, they were unable to get any theatrical dates in America. For some curious reason there seemed to be practically no demand for a German ventriloquist and a woman harpist who yodeled in a foreign language.

Lafe, disappointed at his theatrical reception in the new country, reluctantly decided to abandon show business, and for some inexplicable reason he chose a career as far removed from the theatre as he could conceivably get. Having never repaired an umbrella, he decided, after much deliberation, to become an umbrella-mender…. During one solid year he repaired exactly seven umbrellas for a grand total of $12.50…. Lafe decided to retire from the umbrella-mending business and embark on a new career. The new career consisted of never doing another day’s work until he died, forty-nine years later.

When my grandparents first arrived in America, my grandmother used to play the harp and sing every day. As the reports of her husband’s career in the umbrella-repair business drifted in, the singing gradually ceased. After a while, the little harp was stowed away in the closet never to be heard from again — until one day, Harpo discovered it. Some of the strings were missing and it had no pedals for the sharps and flats; but to a boy whose only musical instrument up to then had been a ten-cent tin whistle, this cheap little harp, by comparison, had all the majesty of a concert piano. In time, Harpo wangled enough money from my mother to get the missing strings replaced. Soon he could play any simple song — unless, of course, it had sharps or flats.

One day the harp disappeared. Harpo was frantic. He searched our flat a dozen times. He searched the halls, the streets, the neighborhood. The harp had vanished as mysteriously as if it had been removed by unseen hands. The fact is, the harp had been removed by unseen hands, but we knew only too well from previous experience that the unseen hands belonged to Chico.

Harpo was inconsolable. Without his beloved harp the world was just an empty planet. My mother’s instructions to my father were brief and direct. “Sam, go to the hockshop on Third Avenue. Somewhere in there you will find the missing harp.”

After much haggling, my father made a deal with the owner of the pawnshop. In exchange for the harp, he promised to tailor a pair of his famous, ill-fitting trousers. Later that day he triumphantly brought the instrument home and put it back in the closet. That done, he proceeded to beat the hell out of Chico. Fortunately for Chico, his hide was made of stern stuff; the occasional beltings he received never seemed to deter him from his constant and frantic search for funds. Chico actually had three homes: the pawnshop, the poolroom and our crowded flat. To the flat he came only for food and shelter.

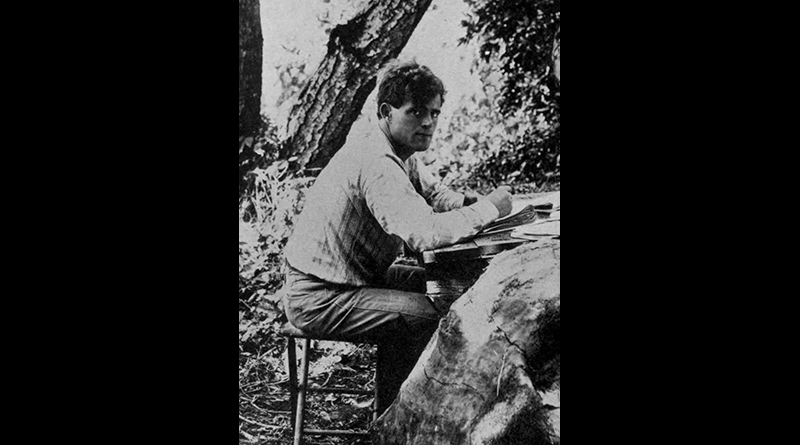

— Groucho Marx, in his autobiography Groucho and Me