My second term at Normandale, at Bexhill-on-Sea, proved to be my last there. I had been sent there as a boarder, at the age of six, shortly after my mother had married David Stiven; and I was blissfully happy, being by far the youngest boy in the school and, consequently, much fussed over. But when the summer term ended I found myself spending a dreary, lonely August holiday confined to a rather gloomy London hotel in the Cromwell Road; a place of unlit Turkey-carpeted passageways, lots of great flowered bowls set in wide mahogany seats with pull-up brass handles for flushing, tinted windows of tulip designs and dusty, green brocaded curtains. Very little air found its way into the hotel; the ferns, in their brass tubs, gave out a fetid smell like dying jungle vegetation. Now and then someone took me for a boring walk in Kensington Gardens, and once I was treated to a visit to the Natural History Museum, but for the most part I was left to my own devices — filling a bath to float a little, lopsided sailing-boat; drawing fierce battle scenes; teasing a tired old maid or building card-houses on the floor of the ‘Residents’ Lounge’. The only positive enjoyment I discovered was being allowed, occasionally, to work the hotel’s water-lift — a slow and stately machine which gurgled its way up and down when you pulled on a greasy rope. Into this contraption, on a morning when I was operating it, there lightly stepped a large foreign lady of advanced years, dressed in threadbare black.

I had doubts whether the water could replace her immense weight; I eyed her like a hangman and then hauled on the rope manfully and successfully. When eventually we reached her floor, after a little upping and downing, she complimented me on my skill; so we became instant friends. She told me, among other interesting things, that she used to be a champion pole-punter in Russia, oh, long before the Revolution; that she had once given a gymnastic display before the Tsar and that as a small girl she walked the tight-rope. A vision filled my head of this new and welcome friend high in the air, wearing a sort of spangled bathing-costume, balancing on a rope with the aid of her punt-pole, while, way down below, crowned heads rose in tumultuous applause. She asked me if I had ever been to the circus. The answer was ‘No’. Had I, perhaps, ever been taken to the theatre? Well, I had seen Chu-Chin-Chow, which I had enjoyed very much; and I gave her half a verse of ‘The Cobbler’s Song’. I had also seen Puss in Boots but had hated it. ‘This must be remedied,’ she said, and instantly proposed taking me the following week to a matinee at the Coliseum, where there was a Variety show. She was as good as her word. She bought seats for the two of us in the Dress Circle. I hate to think, now, what economic heart-searching she must have gone through, rummaging in her vast black bag to see if she had sufficient funds, and wondering, perhaps, if she would have to draw on her meagre savings.

The Coliseum offered jugglers; clowns; maidens in flimsy frocks who danced in flickering lights, attempting to look like flames; a man, with his hands and feet shackled, in a glass tank of water, from which he just managed to escape in a flurry of bubbles; some funnyish men in squashed hats and baggy trousers; acrobats, of course, of whom my hostess was sternly critical; some boring singers; and then — and then — the Top of the Bill, Nellie Wallace.

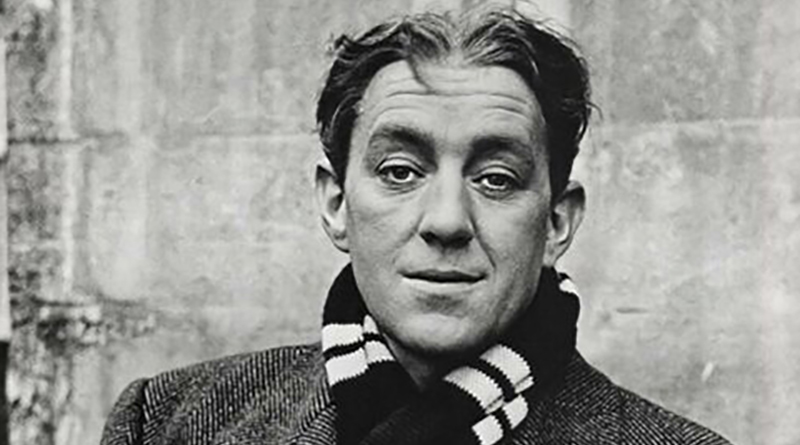

I don’t believe I laughed at Miss Wallace on her first appearance. Truth to tell, I was a little scared, she looked so witch-like with her parrot-beak nose and shiny black hair screwed tightly into a little hard bun. She wore a loud tweed jacket and skirt, an Alpine hat with an enormous, bent pheasant’s feather, and dark woollen stockings which ended in neat, absurd, twinkling button boots. Her voice was hoarse and scratchy, her walk swift and aggressive; she appeared to be always bent forward from the waist, as if looking for someone to punch. She was very small. Having reached centre stage she plunged into a stream of patter, not one word of which did I understand, but I am sure it was full of outrageous innuendoes. The audience fell about laughing but no laughter came from me. I was in love with her. — Alec Guinness, in his autobiography Blessings in Disguise (read for free)