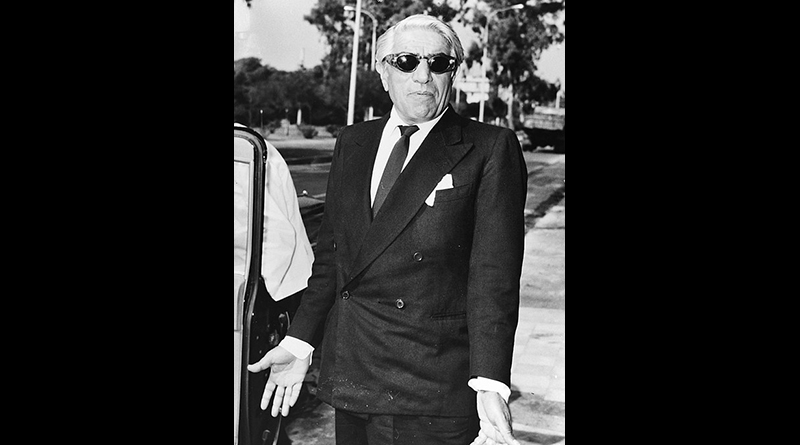

Left Padua at twelve, and arrived at Lord Byron’s country house, La Mira, near Lusina, at two. He was but just up and in his bath; soon came down to me; first time we have met these five years; grown fat, which spoils the picturesqueness of his head…. Found him in high spirits and full of his usual frolicsome gaiety…. He dressed, and we set off together in my carriage for Venice: a glorious sunset when we embarked at Lusina in a gondola, and the view of Venice and the distant Alps (some of which had snow on them, reddening with the last light) was magnificent; but my companion’s conversation, which, though highly ludicrous and amusing, was anything but romantic, threw my mind and imagination into a mood not at all agreeing with the scene….

…I was a good deal struck … by the alteration that had taken place in his personal appearance. He had grown fatter both in person and face, and the latter had most suffered by the change — having lost, by the enlargement of the features, some of that refined and spiritualised look, that had in other times, distinguished it. The addition of whiskers, too, which he had not long before been induced to adopt, from hearing that some one had said he had a faccia di musico , as well as the length to which his hair grew down on his neck, and the rather foreign air of his coat and cap — all combined to produce that dissimilarity to his former self I had observed in him. He was still, however, eminently handsome: and, in exchange for whatever his features might have lost of their high, romantic character, they had become more fitted for the expression of that arch, waggish wisdom, that Epicurean play of humour, which he had shown to be equally inherent in his various and prodigally gifted nature; while, by the somewhat increased roundness of the contours, the resemblance of his finely formed mouth and chin to those of the Belvedere Apollo had become still more striking.

His breakfast, which I found he rarely took before three or four o’clock in the afternoon, was speedily despatched — his habit being to eat it standing, and the meal in general consisting of one or two raw eggs, a cup of tea without either milk or sugar, and a bit of dry biscuit. Before we took our departure, he presented me to the Countess Guiccioli, who was at this time, as my readers already know, living under the same roof with him at La Mira; and who, with a style of beauty singular in an Italian, as being fair-complexioned and delicate, left an impression upon my mind, during this our first short interview, of intelligence and amiableness such as all that I have since known or heard of her has but served to confirm.

…He had all along expressed his determination that I should not go to any hotel, but fix my quarters at his house during the period of my stay; and, had he been residing there himself, such an arrangement would have been all that I most desired. But, this not being the case, a common hotel was, I thought, a far readier resource; and I therefore entreated that he would allow me to order an apartment at the Gran Bretagna, which had the reputation, I understood, of being a comfortable hotel. This, however, he would not hear of; and, as an inducement for me to agree to his plan, said that, as long as I chose to stay, though he should be obliged to return to La Mira in the evenings, he would make it a point to come to Venice every day and dine with me. As we now turned into the dismal canal, and stopped before his damp-looking mansion, my predilection for the Gran Bretagna returned in full force; and I again ventured to hint that it would save an abundance of trouble to let me proceed thither. But ‘No — no,’ he answered — ‘I see you think you’ll be very uncomfortable here; but you’ll find that it is not quite so bad as you expect.’

As I groped my way after him through the dark hall, he cried out. ‘Keep clear of the dog’; and before we had proceeded many paces farther, ‘Take care, or that monkey will fly at you’; — a curious proof, among many others, of his fidelity to all the tastes of his youth, as it agrees perfectly with the description of his life at Newstead, in 1809, and of the sort of menagerie which his visitors had then to encounter in their progress through his hall. Having escaped these dangers, I followed him up the staircase to the apartment destined for me. All this time he had been despatching servants in various directions — one, to procure me a laquais de place , another, to go in quest of Mr Alexander Scott, to whom he wished to give me in charge; while a third was sent to order his Segretario to come to him. ‘So then, you keep a Secretary?’ I said. ‘Yes,’ he answered, ‘a fellow who can’t write — but such are the names these pompous people give to things.’

When we had reached the door of the apartment it was discovered to be locked, and, to all appearance, had been so for some time, as the key could not be found; — a circumstance which, to my English apprehension, naturally connected itself with notions of damp and desolation, and I again sighed inwardly for the Gran Bretagna. Impatient at the delay of the key, my noble host, with one of his humorous maledictions, gave a vigorous kick to the door and burst it open; on which we at once entered into an apartment not only spacious and elegant, but wearing an aspect of comfort and habitableness which to a traveller’s eye is as welcome as it is rare. ‘Here,’ he said, in a voice whose every tone spoke kindness and hospitality — ‘these are the rooms I use myself, and here I mean to establish you.’

— Thomas Moore, in “Moore Recalls His Visit” from the book Byron: Interviews and Recollections