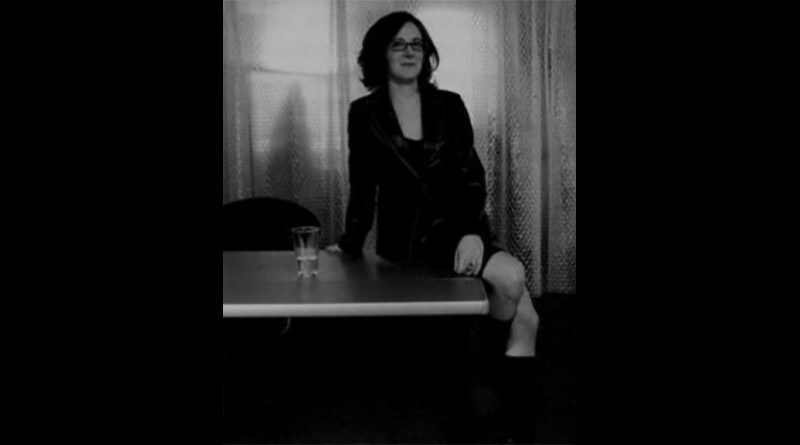

When I get back, [David] Bailey is at the camera; Marianne, in a black mac and fishnet tights, is sprawling with her legs wide apart, her black satin crotch glinting between her scrawny fifty-five-year-old thighs, doing sex-kitten moues at the camera. ‘Oh please, stop!’ I want to cry — this is sadism, this is misogyny, this is cruelty to grandmothers. I wonder if Bailey actually hates her — I wonder if this is her punishment for turning up late. I hear the agent and the Frenchman muttering behind me: ‘They won’t use this, they can’t.’ So why is Bailey shooting it then?

Suddenly, the session is over, and we — Marianne, the Frenchman, the PR and me — emerge into the street where a chauffeur-driven limousine has been waiting all this time. It is now 6:45 p.m. and Faithfull has still barely said hello. The PR says we can eat at the Italian restaurant at the end of the street. Marianne says she can’t possibly walk, so we pile into the limousine to drive 50 yards to the corner. It is a sweet, friendly, family-run Italian restaurant that has no idea what hell awaits it. No sooner have we been ushered into a private room downstairs than Marianne is muttering, ‘What do you have to do to get a drink around here?’ Order it, seems the obvious answer, but that’s too simple — Francois has to order it for her. Unfortunately — my huge mistake — I have let him and the PR eat downstairs with us, albeit at a separate table, and even more unfortunately I have placed Marianne against the wall, where she can see Francois over my shoulder. I could smack myself: what’s the use of serving all these years in the interviewing trenches if I still make such elementary mistakes?

Suddenly, Marianne is shouting at Francois, ‘Get it together!’ and he is shouting back, ‘What do you want, Marianne?’ ‘I don’t know. What have they got?’ she counters, drumming her feet under the table and moaning, ‘I. Can. Hardly. Bear. It.’ Francois keeps asking whether she wants wine or a cocktail. I’m thinking rat poison. Eventually she tells Francois a bottle of rose. The waiter brings it with commendable speed and starts pouring two glasses. She snatches mine away — ‘We don’t need that. Where’s the ice bucket?’ The waiter goes away and comes back with an ice bucket. ‘I’ll have the veal escalope,’ she tells him. He waits politely for my order. ‘Veal! Vitello!’ she snaps — she can’t understand why he is still hanging around when he should be off escaloping veal. ‘I’ll have the same,’ I say wearily.

I’m already fed up with her and we haven’t even started. But at this point — a tad late, in my view — she suddenly flicks the switch marked ‘Charm’ and bathes me in its glow. ‘Cheers!’ she says. ‘Sorry I yelled. A slight crise there. It’s been a long day.’ (Really? She was still in bed at one, it is now seven, hardly a full shift at the coalface.) But anyway, she is — finally — apologetic. And I in turn put on my thrilled-to-meet-you face and tell her that I deeply enjoyed her autobiography Faithfull (1994), which I did. It is a truly amazing story — a pop star at seventeen, a mother at eighteen, Mick Jagger’s girlfriend at nineteen, reigning over Cheyne Walk and yet by her thirties she was a heroin addict living on the street in Soho. Even if she didn’t write a word of it (David Dalton was co-author), she deserves some credit just for living it. For a while she basks in my compliments and then switches off the charm and snaps, ‘But I’m not going to talk about the book, I want to talk about the film.’ Huh? Too late I realise my mistake with the placement — obviously there has been some signal from Francois. — Lynn Barber, in her book A Curious Career (read for free)