When I was in high school, in Lancaster, I formed my first band, the Black-Outs. The name derives from when a few of the guys, after drinking peppermint schnapps, purchased illicitly by somebody’s older brother, blacked out.

This was the only R&B band in the entire Mojave Desert at that time. Three of the guys (Johnny Franklin, Carter Franklin and Wayne Lyles) were black, the Salazar brothers were Mexican and Terry Wimberly represented the other oppressed peoples of the earth.

Lancaster was a boomtown then. There was a huge influx of technical employees (guys like my Dad) who had dragged their families into this godforsaken place in order to work on the missile projects at Edwards Air Force Base. The original inhabitants, sons and daughters of alfalfa farmers and feed-store owners, held all the newcomers in low esteem. We were the people from “down below” — a term used to describe anyone who was not from the high desert area where Lancaster was located.

The pecking order at the high school was pretty well laid out: members of the social elite (the lettermen and cheerleaders) were all reproductive by-products of the coots and codgers that ran the local feed and grain business. The lowest rung on the ladder in this 1957 social arrangement was reserved for the sons and daughters of the black families who raised turkeys in an area beyond Palmdale — Sun Village. Only slightly above that rung was a little slot for the Mexicans.

The fact that this was an “integrated” band disturbed a lot of people. This distress was compounded by the fact that, prior to my arrival, someone had put on a rhythm-and-blues show at the fairgrounds, and legend had it that “colored people brought dope into the valley when they did that damn show, and we’re never gonna let that kind of music ’round here again.”

I didn’t know about any of this shit when I put the band together. Anyway, my part-time job in high school was working in a record store for a nice lady named Elsie (sorry, I can’t remember her last name) who liked R&B. As you can imagine, in a town like that, paying gigs for an “integrated R&B band” were few and far between. One day, I got a great idea: I decided to promote my own gig — a dance — at the local women’s club hall, and I asked Elsie to help me. I wanted her to rent the hall for us, and she agreed to do so. Now, I’m pretty sure about this — it was Elsie who had promoted the original “colored-person show with optional chemical commodities” — and I didn’t fully grasp the local sociopolitical ramifications of all this when I asked her to book the hall.

So, everything was set — the band rehearsed out in Sun Village in the Harrises’ living room, we had our song list, we were selling tickets, everything was fine. The evening before the dance, while walking through the business district at about six o’clock, I was arrested for vagrancy. I was kept overnight in the jail. They wanted to keep me long enough to cancel the dance — just like in a really bad 1950s teenage movie. It didn’t work. Elsie and my folks got me out.

We played the dance. It was a lot of fun. We had an enormous turnout of black students from Sun Village. Motorhead Sherwood was the hit of the evening — he did this weird dance called “The Bug,” where he pretended that some creature was tickling the fuck out of him, and he rolled around on the floor, trying to pull it off. When he ‘got it off,’ he threw it at girls in the audience, hoping that they would flop around on the floor too. A few of them did.

After the dance, as we were packing our stuff into the trunk of Johnny Franklin’s wasted blue Studebaker, we found ourselves surrounded by a large contingent of lettermen (The White Horror), eager to cause physical harm to our disgusting little ‘integrated band.’ This was a mistake because, upon seeing the Gathering of the Ugly Jackets, a few dozen ‘Villagers’ started hauling chains and tire irons out of their trunks, with a look in their eyes that said, “The night is young.”

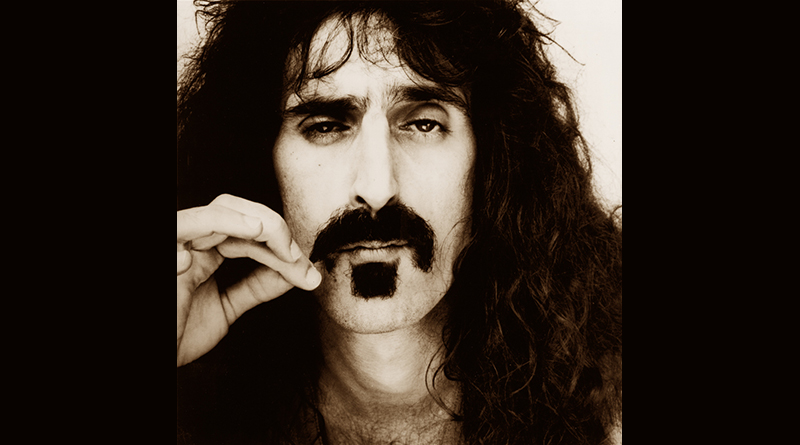

The lettermen folded, in total humiliation — God, they’re so sensitive about that sort of thing — and went home to their coots and codgers. They remained hostile to me and the other guys in the band all the way through to graduation. — Frank Zappa, in his autobiography The Real Frank Zappa Book (read for free)