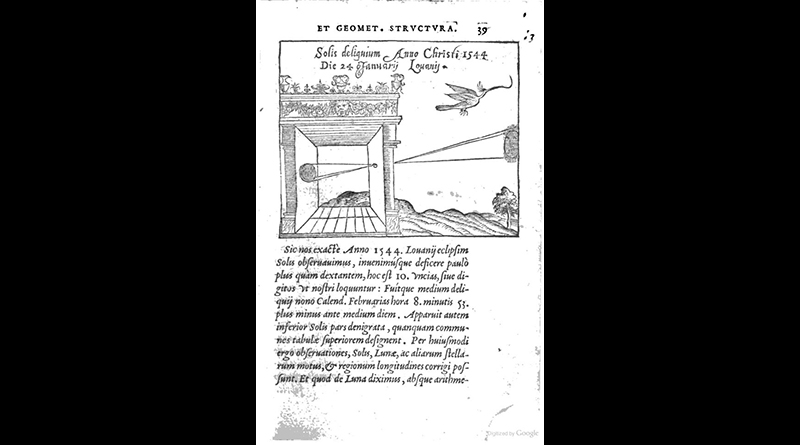

The thesis I am putting forward here is that from the early fifteenth century many Western artists used optics — by which I mean mirrors and lenses (or a combination of the two) — to create living projections. Some artists used these projected images directly to produce drawings and paintings, and before long this new way of depicting the world — this new way of seeing — had become widespread. Many art historians have argued that certain painters used the camera obscura in their work — Canaletto and Vermeer, in particular, are often cited — but, to my knowledge, no one has suggested that optics were used as widely or as early as I am arguing here.

In early 1999 I made a drawing using a camera lucida. It was an experiment, based on a hunch that Ingres, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, may have occasionally used this little optical device, then newly invented. My curiosity had been aroused when went to an exhibition of his portraits at London’s National Gallery and was struck by how I small the drawings were, yet so uncannily ‘accurate’. I know how difficult it is to achieve such precision, and wondered how he had done it. What followed led to this book.

At first, I found the camera lucida very difficult to use. It doesn’t project a real image of the subject, but an illusion of one in the eye. When you move your head everything moves with it, and the artist must learn to make very quick notations to fix the position of the eyes, nose and mouth to capture ‘a likeness’. It is concentrated work. I persevered and continued to use the method for the rest of the year — learning all the time. I began to take more care with lighting the subject, noticing how a good light makes a big difference when using optics, just like with photography. I also saw how much care other artists Caravaggio and Velazquez, for example — had taken in lighting their subjects, and how deep their shadows were. Optics need strong lighting, and strong lighting creates deep shadows. I was intrigued and began to scrutinize paintings very carefully. — David Hockney, in his book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (read for free)